Historical Heroines: Poet Li Qingzhao 李清照 (1084 AD - c. 1155 AD)

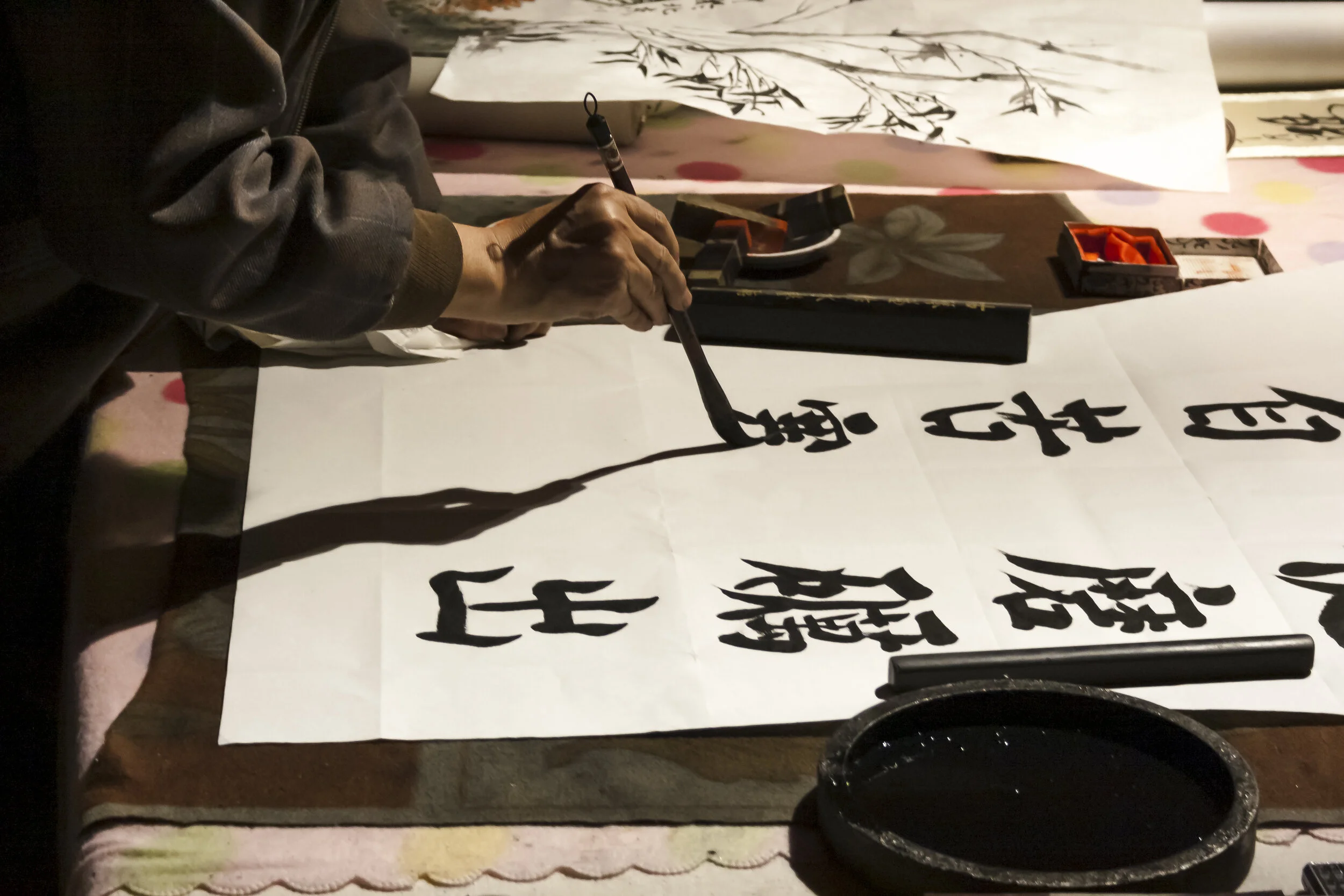

(Photo: Yang Shuo/Unsplash)

Spending a lot of time on the Internet researching my novel has led me down some very interesting paths and discovering some fascinating figures in history, and one figure who recently impacted me is the poet and essayist Li Qingzhao (李清照), pesudonym Yi’an (易安居士), who lived and died during the Song Dynasty in China.

I can’t fairly say I discovered her, as she is one of the most famous poets of Chinese antiquity. However, I did only learn about her very recently, even though I’ve felt her impact long before I knew her name. She captured my imagination because while her time on this earth precedes ours by almost a thousand years, her words, her story, even the emotions she left behind feel as tangible as though she lived yesterday.

(Photo: Dan Ma/Unsplash)

Li Qingzhao was born into a family of scholars in 1084 AD in what is now modern day Shandong province. Her father was also a high-ranking official for the government and a man of letters, and her mother was also from a family of esteemed writers and poets. As a result, she received a comprehensive literary education from her family’s extensive library from when she was just a young girl, and was thoroughly accomplished in history, poetry, calligraphy, and music in a time when only a tenth of women could read.

By the time she was a young teenager, her poetry was already read widely in her hometown. She specialized in various forms of poetry, but her lyrical “ci” poems were praised for their restraint and refinement. She was adept in evoking emotions with acute imagery. Snow, rain, birds, rivers, flowers, fruit all populate Li Qingzhao’s poems in stunning relief. Most of her writing is lost to time, and only about 50 of her “ci” poems survive.

(Photo: Marco Zuppone/Unsplash)

To demonstrate, Jiaosheng Wang translates one of the stanzas of Li Qingzhao’s most famous poems “Spring at Wu Ling” in his book “The Complete Ci-poems of Li Qingzhao: A New English Translation”:

“I hear 'Twin Brooks' is still sweet

With the breath of spring.

How I'd, too, love to go for a row,

On a tiny skiff. But I fear at 'Twin Brooks'

My grasshopper of a boat

Wouldn't be able to bear

Such a load of grief.”

(Photo: Arisa Chatassa/Unsplash)

At age 17, Li fell in love and married 21-year-old Zhao Mingcheng, the third son of the prime minister. The pair were considered the golden literary couple of their time, and were very happy together. They shared a great love for art and amassed an enormous collection of antiquities to preserve for history. In her epilogue for her husband’s magnum opus “Records on Metal and Stone” translated by Stephen Owen in “Anthology of Chinese Literature,” she recounts such happy evenings spent in their library, drinking tea, and playing games:

I happen to have an excellent memory, and every evening after we finished eating, we would sit in the hall called “Return Home” and make tea. Pointing to the heaps of books and histories, we would guess on which line of which page in which chapter of which book a certain passage could be found. Success in guessing determined who got to drink his or her tea first. Whenever I got it right, I would raise the teacup, laughing so hard that the tea would spill in my lap, and I would get up, not having to been able to drink any of it at all. I would have been glad to grow old in such a world. Thus, even though we were living in anxiety, hardships, and poverty, our wills were not broken.

(Photo: Christian Joudrey/Unsplash)

But their happy days were cut short when the Jin Tartars attacked the capital in 1127, and the family packed up the many, many articles of their collection and made the move south. According to Li, “We could not take the overabundance of our possessions with us, we first gave up the bulky printed volumes, the albums of paintings, and the most cumbersome of the vessels. Thus we reduced the size of the collection several times, and still we had fifteen cartloads of books…In our old mansion in Qing-zhou we still had more than ten rooms of books and various items locked away.” Eventually, Qing-zhou was razed and they lost everything. What followed was two years of nomadic-like roaming. First the pair settled Jian-Kang Prefecture and then intended to take up lodging on the river Gan, but then in the summer of 1128, Zhao was summoned for an audience with the emperor before he was to take up the governorship of Hu-zhou.

(Photo: Godslar/Unsplash)

Her husband set off on his own on August 13, Li describes the day vividly, “He sat there on the bank, in summer clothes with his headband high on his forehead, his spirit like a tiger’s, his eyes gleaming as though they would shoot into a person, while he gazed toward the boats and took his leave. I was terribly upset. I shouted to him, ‘If I hear the city is in danger, what should I do?’ He answered from afar, hands on his hips: ‘Follow the crowd. If you can’t do otherwise, abandon the household goods first, then the clothes, then the books and scrolls, then the old bronzes—but carry the sacrificial vessels for the ancestral temple yourself. Live or die with them. Don’t give them up!’ With this he galloped off on his horse.” This was the last time she was to see her husband in good health. Along his journey, he contracted malaria and eventually passed away from dysentery on October 18. Li managed to reach his side before he died, but after he was gone, he left her with no provision for the future. She had only their books, but even those, not for long.

(Photo: Zhengfan Yang/Unsplash)

She sent the books along to her brother-in-law, who was the Ministry of War in Hong-zhou, but the Jin Tartars sacked the city the following February and all were lost. She had only a few belongings left, and as the political situation continued to deteriorate, she had nowhere to go. She roamed from place to place, shedding possessions as she went. “All that remained were six or so baskets of books, paintings, ink and instones that I hadn’t been able to part with. I always kept these under my bed and opened them only with my hands,” she wrote. But one night, as she was lodging at an inn, someone stole five of the baskets through a hole in the wall as she slept. After much searching, she found they had been sold to someone else.

Eventually, Li lost almost everything, but the one thing she protected with her life was her husband’s manuscript for “Records on Metal and Stone.” That, she carried with her, carefully edited it, wrote the afterword, and had it published posthumously. In her epilogue, she rued the days when her husband could leisurely curate their collection, how he would carefully bind and write his imprint on each book: “It is so sad—today the ink of his writing seems still fresh, but the trees on his grave have grown to an armspan in girth.”

(Photo: Jiawei Chen/Unsplash)

Not much is known about what happened to Li after the publication of the book. There are stories that she remarried, but her new husband was abusive and so she successfully sued him for divorce, but none of this is confirmed. We have some of her poems from the latter half of her life, and they are markedly different from the girlish naivete of her earlier verses. One written after she fled to the south, where the banana trees grow, is aptly titled “Banana Trees.” It abridges well some of the loneliness she must have felt:

“Who planted the banana trees in front of my casement,

Filling the courtyard with shadows,

With shadows?

Each leaf a heart brimming over with love

As it closes or unfolds.

Patter of midnight rain on the leaves

Haunting the pillow—

Dripping ceaselessly,

Dripping ceaselessly.

Dismal sounds, painful memories:

An outcast from the North in the throes of sorrow

Cannot bear to sit up and listen.”

She died sometime after 1155, far away from home.

References:

Wang, Jiao Sheng. (1989). The Complete Ci-poems of Li Qingzhao: A New English Translation.

Sino-Platonic Papers (Number 13), pg. 117. Retrieved from http://sino-platonic.org/complete/spp013_li_qingzhao.pdf

Owen, Stephen. Anthology of Chinese Literature. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1996 Print.

Stay in touch! Follow me on Instagram and Facebook to be the first to know when I post.

(Featured photo: Annie Spratt/Unsplash)